Today’s Untrained Yet Truly Morbid Fact!

During the dry summer and fall of 1933, thousands of workers financed by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation were hired to clear dry brush and to build trails and roads in Griffith Park in Los Angeles. On October 3, 1933, an estimated 3,780 men were working in the park in more than 100 squads of 50 to 80 men, each supervised by a foreman or “straw boss”.

A little after 2 p.m., a small fire started in a pile of debris in Mineral Wells Canyon. Many of the workers volunteered or were ordered to fight the fire, but it spread up the canyon. Because there was no piped water in the area, the men tried to beat out the fire with shovels. Foremen with no knowledge of firefighting initially directed the effort, setting inappropriate back fires and sending hundreds of workers into a steep canyon.

Fire Chief Ralph Scott said when firefighters arrived they found an estimated 3,000 workers in a 40-acre fire area that included Mineral Wells Canyon, nearby Dam Canyon and the ridge that separated the two. The workers were making well-intentioned but often inefficient efforts to contain the blaze. Chief Scott said his men could not effectively fight the fire and ensure the welfare workers’ safety at the same time, largely because they had no way to control the workers’ actions. “It was absolutely impossible for firemen to control them because of their great numbers,” he said.

A working class hero is something to be…

Around 3 p.m., the wind–which had been blowing gently and steadily down the canyons from the northwest–shifted. The fire advanced on the workers quickly, taking them by surprise. Said Richard D. Meagher, a foreman, “Suddenly there was kind of a whirlwind and the fire broke loose.” It jumped a fire break some workers had hastily made in the canyon.

Some of the foremen rode their workers hard to hold the line. One worker said he and his work gang were “being yelled at like a bunch of cattle.” When another worker, L. J. Green, decided to retreat from the flames, a foreman yelled at him to “get the hell back in there.” Worker Frederick Alton saw a man running away from the fire struck on the jaw by a foreman and knocked down.

But as the flames crept closer, survival instinct took over. Most of the men ran directly away from the fire, climbing up and out of the canyon. Others chose to run sideways to the rapidly-advancing flames. This route required no climbing and provided fairly quick access to the main road. As it turned out, this second choice–for the workers who had a choice–was the better of the two.

Running directly away from the flames meant running downwind and uphill. This was a deadly mistake. Even the most able-bodied men could only climb up and out of the canyon at two or three miles per hour. Witnesses said that the wind was pushing the fire up the canyon wall at up to 20 miles per hour.

Men scrambled madly up the canyon wall, trying to outrun the advancing flames. Workers watching from the new road above heard a particularly grisly transcript of the proceedings. “You could tell the progress of the fire by the screams,” said John Secor. “The flames would catch a man and his screams would reach an awful pitch. Then there would be an awful silence. Then you would hear somebody scream and then it would be silent again. It was all over inside of seven minutes.”

It was a few minutes after 3 p.m. That much is well pinpointed because in some cases the dead workers wore watches that stopped when the flames reached them.

Meantime, some of the men in Dam Canyon weren’t just being chased by the fire–they were surrounded by it. “I didn’t know if I was going away from the fire or toward it, because we were hemmed in by flames,” said G. B. Carr. Just how some of the workers became surrounded was a key topic of the inquests.

Some of the men tried diving through the advancing wall of flame like it was an ocean wave. “I heard someone yell “Look out!” and a wall of flames was on us,” said Anton Schaefer. He was cutting away brush in a ravine with some other men. “It was exactly like the big waves of the ocean came over you, except it was fire. The only way out was straight up the hill in front. It looked like a cliff.”

Some survived in unique ways. Miguel Holquin, originally listed among the dead, survived by jumping into a stone planter he was building around an oak tree and covering himself with sand. Several men dove into the swimming pool at what was then the girls’ camp, and survived.

Fate, intuition or maybe just luck played a role. Foreman H. N. Claypool was about to order his 20-man crew to cut a fire break, then decided against it. “Something told me to stop,” he said. Shortly afterward, a tornado of flame swept over the place they were headed. “Six or eight men in the squad just beyond us were trapped,” Claypool said.

Then it stopped. The fire department had the blaze under control before nightfall.

Because of the disorganized nature of the deployment and the often inaccurate recordkeeping of the work project, it took weeks to establish the exact death toll and identify the bodies. A month after the fire, the District Attorney’s office put the official death toll at 29, although other groups claimed the number was 52 or higher. The Griffith Park fire was the deadliest in the State’s history until the 2017 California wildfires. The cause of the fire was never determined.

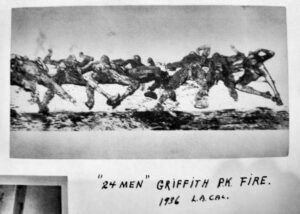

Three photographs of the charred corpses (“24 Men”) c

ulled from Death Scenes: A Homicide Detective’s Scrapbook:

Culled from: Wikipedia and Los Angeles Fire Department Historical Archive